Compostlight

2023/24

Wood, cardboard, motor, mirrors, lightbulbs, magnifying lenses, and onion skin paper

Various dimensions

The kinetic light installation at the entrance to the exhibition Offerings for Escalante offers an in-between place for contemplation. It is inspired by a festive disco light Enzo Camacho and Ami Lien encountered on a bungkalan site in Negros. Bungkalan, which means literally “to cultivate,” refers to local farmers’ collective action of occupying small plots of land to grow diverse crops for their own sustenance, specifically in the context of disputes over the state’s policy regarding land reform. Through a delicate assemblage of lenses and mirrors, intricate patterns of translucent onionskins are projected onto the surrounding walls and move in a circular flow that neither encloses nor contains. It invitingly unfurls itself to the infinite depth of grief, hope, or any other desires and states of mind that seek to enter. Its openness signals that the history of the land, and the manifold stories of people’s relationships to the land, have neither a beginning nor an end. What Compostlight offers is a fragmentation of perspectives, a memory device for multiplying shapes and forms, turning waste matter into a nutrient-rich soil for the emergence of storylines and imaginaries of what is yet to come.

On the Paper Compositions

The seven handcrafted paper compositions were produced by Camacho and Lien entirely in Berlin, using foraged natural materials the artists had gathered during their research trips on the island of Negros, including bagasse (sugarcane fiber), banana stalk, coconut husk, cogon grass, sargassum algae, taro shoot, and seashell. Over the past few years, the artists have organized paper-making workshops with local communities in the Philippines and elsewhere, developing a collaborative creative process based on mutual learning and knowledge sharing. Their working process involves a series of intricate steps and elaborate techniques—from boiling and processing plant matter and making paper from wet pulp to applying multiple layers of wax and paint. These practices are reminiscent of the successive labor process of preparing the soil for growing crops, like composting, ploughing, burning and weeding. The tactile, vivid aesthetic of the compositions speaks to the abundant multitude of offerings from the land and from the communities, culminating in kaleidoscopic images of alternative landscapes. Far from becoming elevated objects of art removed from their referential site, these paper works collapse the mappable distance between places, temporalities and social contexts. They reorganize knowledge of relations beyond the categories of history and ecology as we know them, in order to gesture toward our shared struggles and strivings beneath the cartographic surface of land and sea.

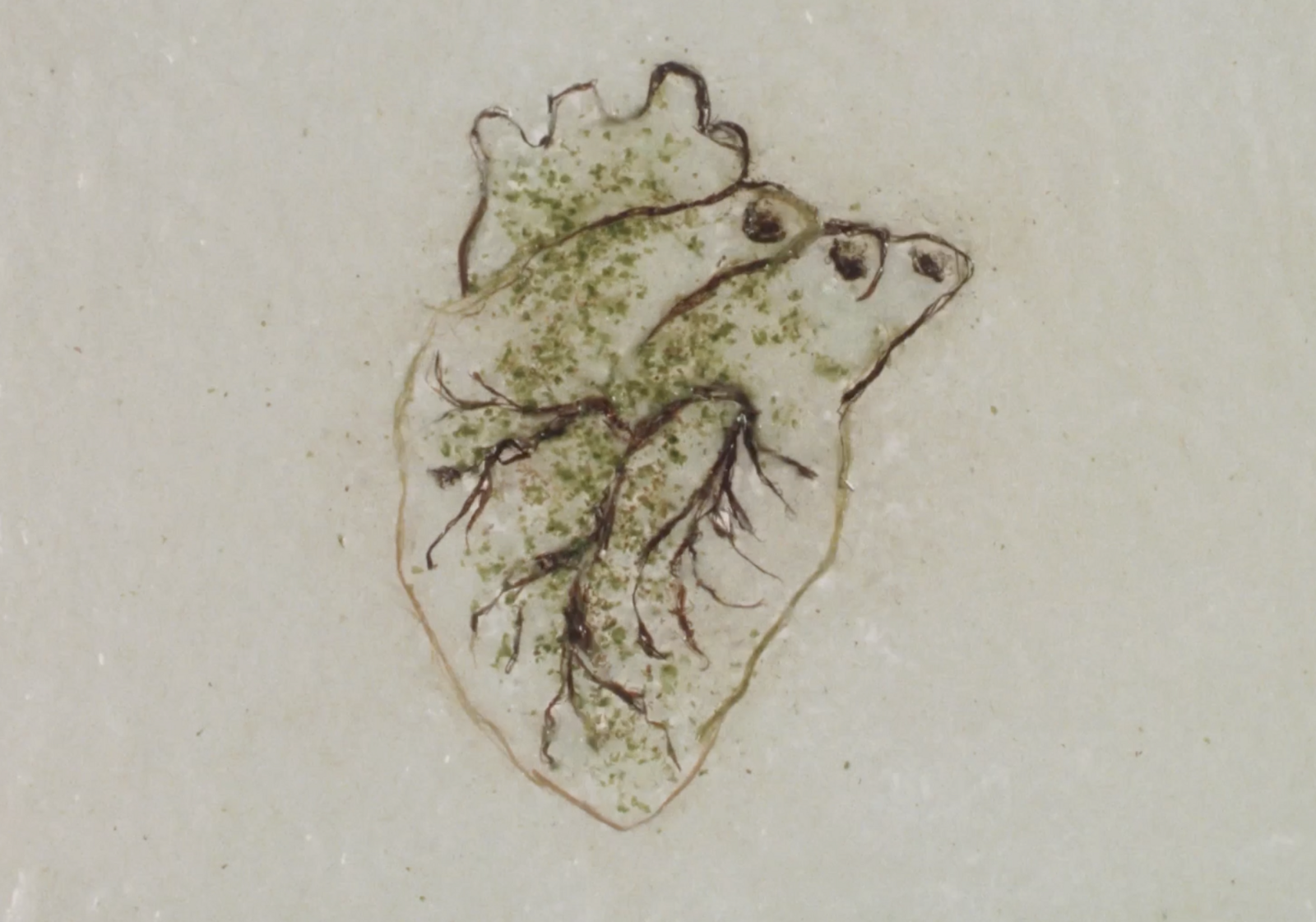

Sacred Heart (sanctuary)

2024

Watercolor, ink, beeswax, abaca pulp, bagasse (sugarcane fiber), cilantro, fennel, kenaf, mica, nipa palm, seaweed

120.7 × 99.7 × 11.4 cm

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Sacred Heart (sanctuary), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Camacho and Lien’s research on the plantation island of Negros began with The Angry Christ—a queer church mural painted in 1950 by the Filipino American artist Alfonso Ossorio, commissioned for the Catholic worker’s chapel within an industrial sugar mill compound. The chapel was originally built with the intention to assimilate religious life into the smooth operation of the plantation economy, and to prevent social unrest and potential insurrection among the workers. The intense, visceral energy of Ossorio’s mural and its unforeseen potential to defy this spiritual agenda of the neocolonial regime inspired the artists both visually and politically. Sacred Heart (sanctuary) draws from The Angry Christ’s motifs and vivid colors as well as the stained glass of the Kaiser-Wilhem-Gedächtniskirche in Berlin, channeling the disruptive figure from afar while responding to the immediate surroundings of the exhibition. It brings distant places into contact and weaves together different pasts of rupture and renewal.

Alfonso Ossorio, The Angry Christ, church mural, 1950, Negros, Philippines, courtesy the artists.

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Sacred Heart (sanctuary), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

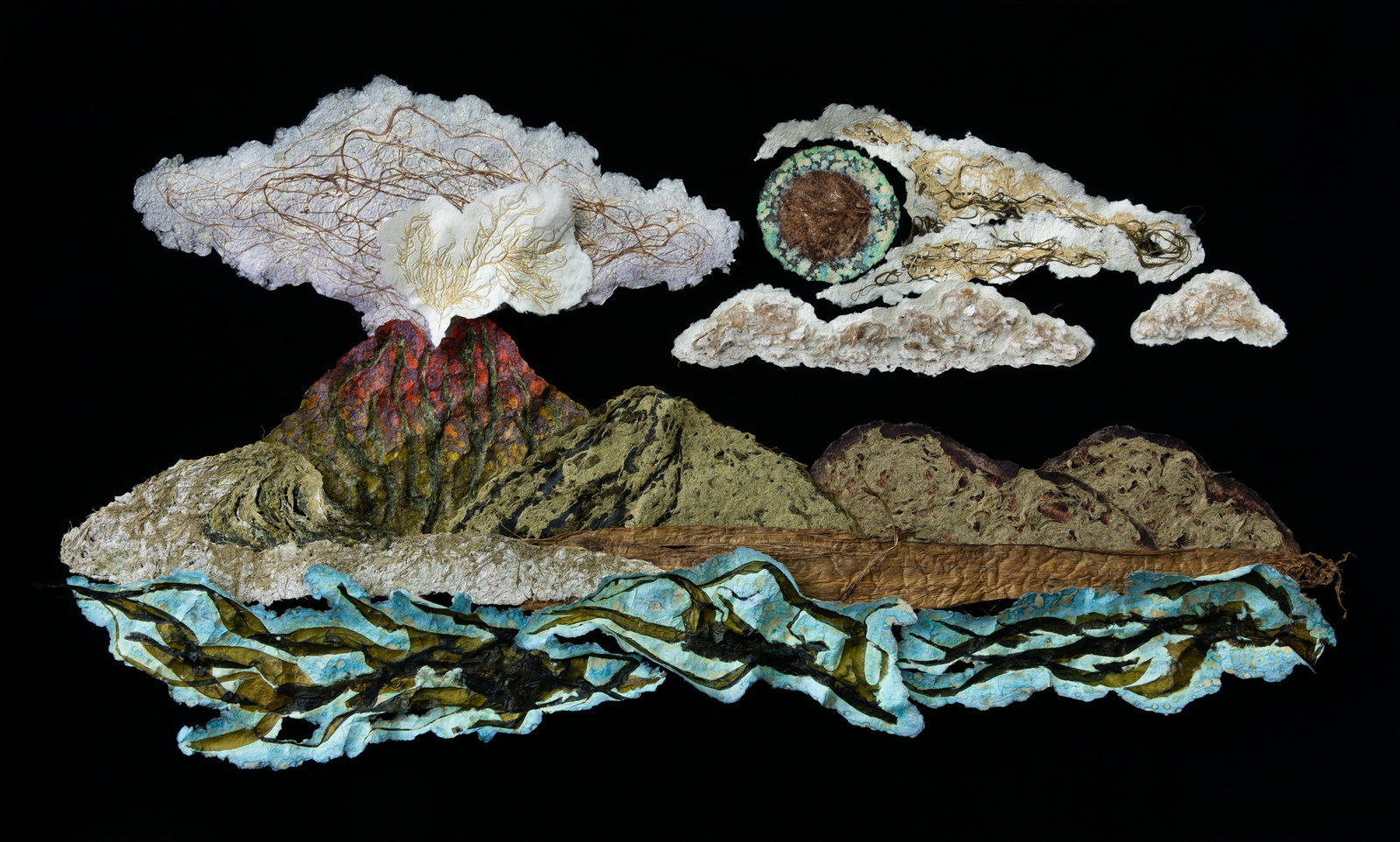

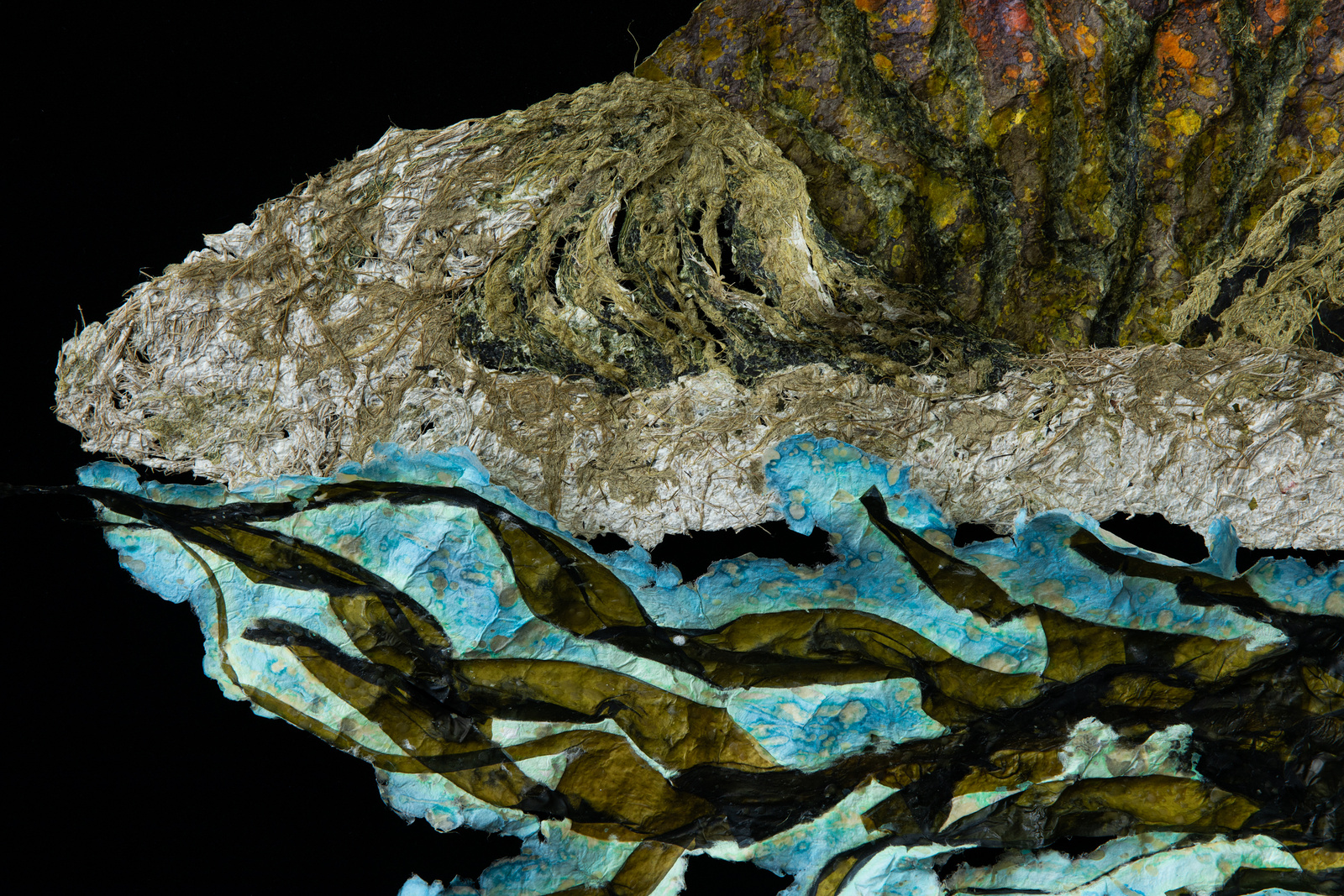

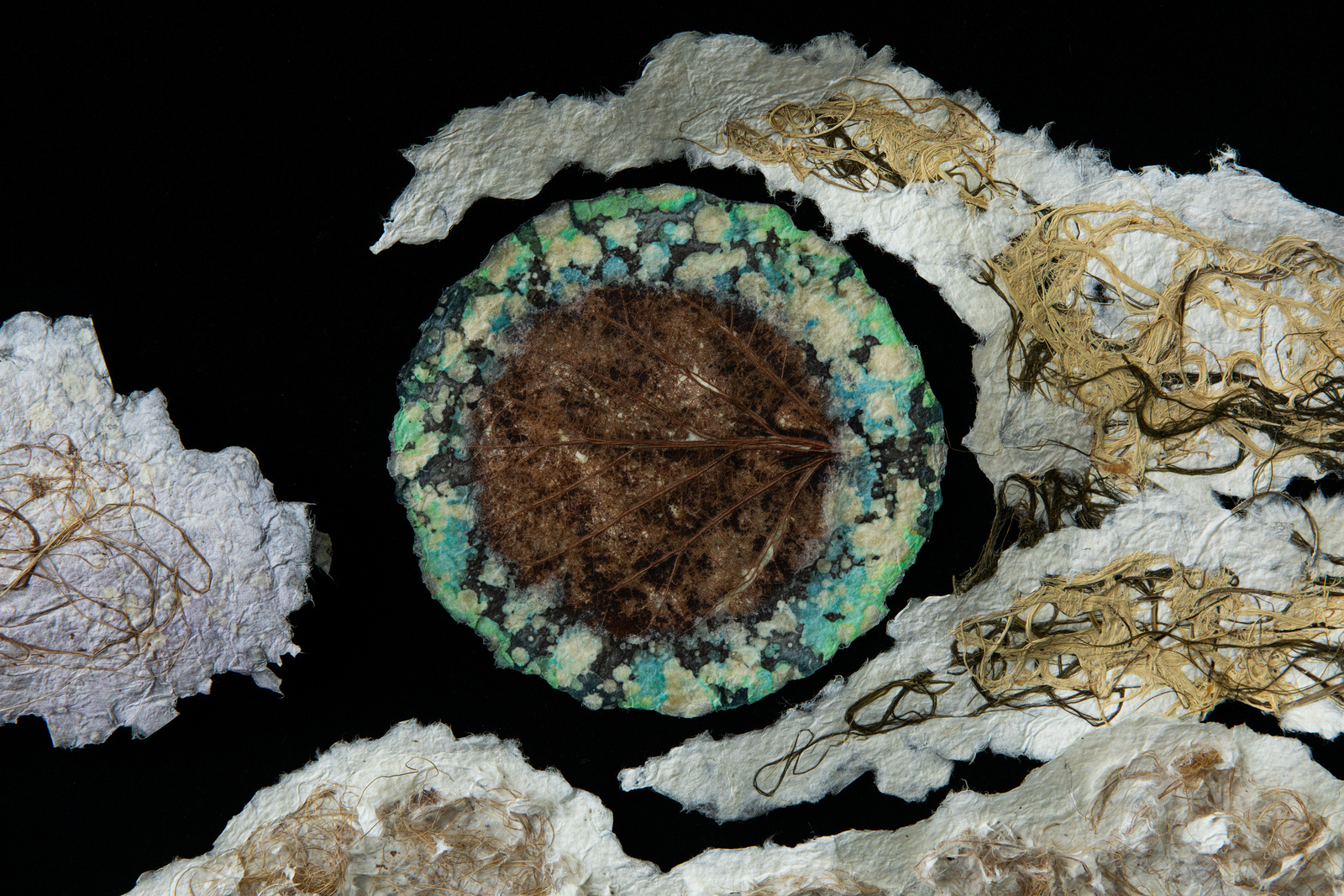

Social Volcano (restless waves)

2024

Watercolor, beeswax, abaca pulp, bagasse (sugarcane fiber), banana stalk, coconut husk, cogon grass, lemongrass, mica, pineapple tops, sugarcane leaves, water spinach, seashell, seaweed, and taro shoots

93.3 × 154.3 × 11.4 cm

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Social Volcano (restless waves), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

The constant famine that had plagued Negros throughout the 1980s and the increasing political oppression against farmers’ protest all resulted in a climate of high tension and turbulence, described by local bishop and liberation theologist Antonio Fortich as a “social volcano.” Its climactic eruption was marked by a nationwide mass protest in 1985, which led to the tragic massacre in Escalante. This widespread metaphor is taken up by Camacho and Lien in a striking landscape titled Social Volcano (restless waves), embodying a moment of rupture that irreversibly shaped the island’s history. On the northern part of Negros lies Mount Kanlaon—the highest peak of the island and an active volcano that finds itself at the heart of both ancient mythologies and modern tales of revolution. The island’s topography thus becomes an inscription of time; landscape itself is history.

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Social Volcano (restless waves), 2024, details. Photos: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

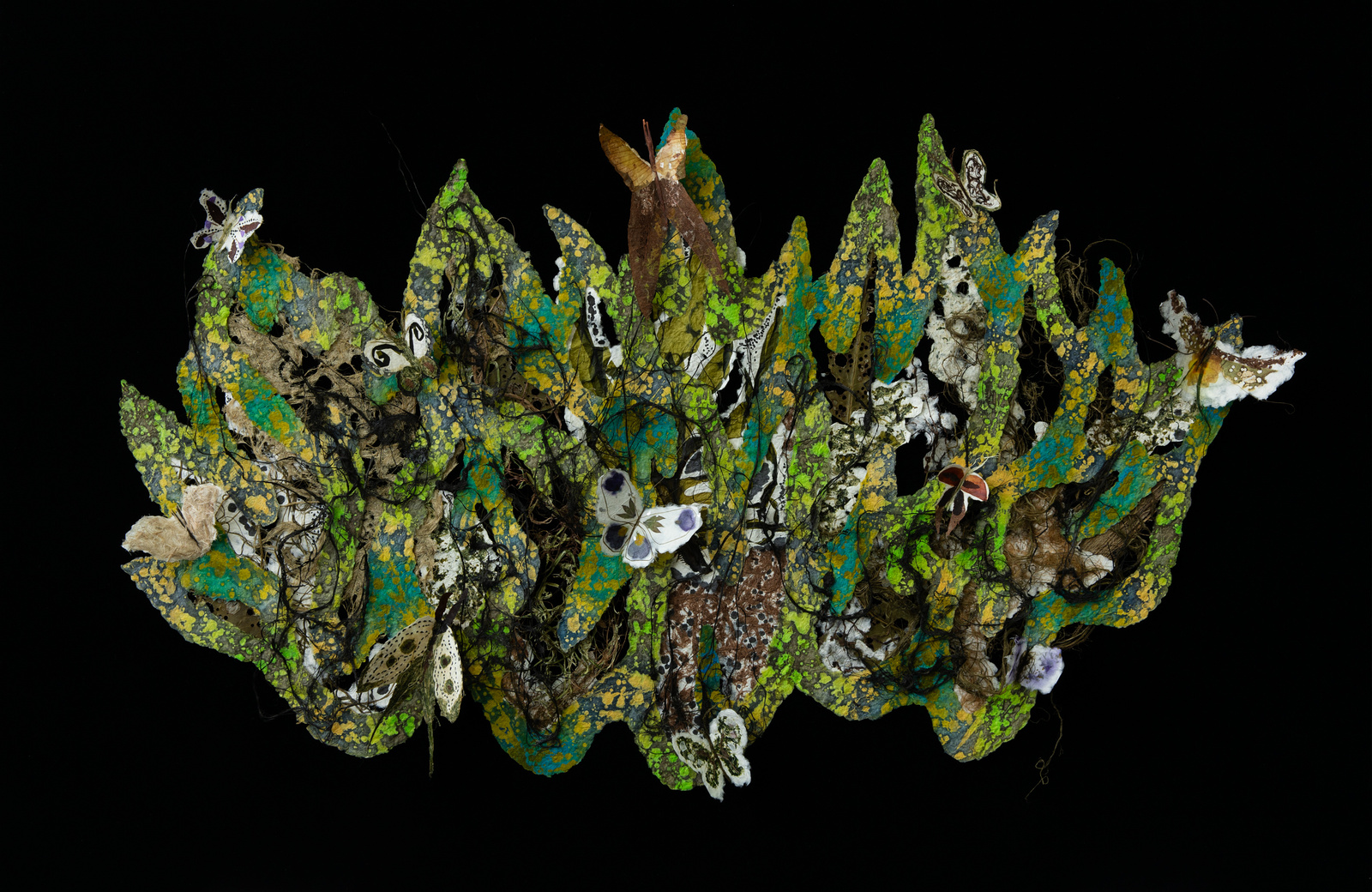

Flame Garden (bruised)

Flame Garden (enzyme)

2024

Watercolor, ink, beeswax, abaca pulp, bagasse (sugarcane fiber), banana stalk, cilantro, coconut, cogon grass, fennel, kale, leek, onion skins, primrose petals, rice hull, sargassum algae, seashell, seaweed, spring onion, statice blossoms, and taro shoots

80.6 × 122.6 × 11.4 cm

2024

Watercolor, ink, beeswax, abaca pulp, bagasse (sugarcane fiber), banana stalk, cilantro, coconut, cogon grass, fennel, kale, leek, onion skins, primrose petals, rice hull, sargassum algae, seashell, seaweed, spring onion, statice blossoms, and taro shoots

80.6 × 122.6 × 11.4 cm

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Flame Garden (bruised), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Flame Garden (enzyme), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Flame Garden (bruised), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Flame Garden (enzyme), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

As a tool for farming, fire is used to clear the field for next season’s crops. Here, the fires are not simply a destructive, cleansing force. They are intertwined with delicate butterflies that are seemingly fragile, yet are bursting forth from the flames. Manifesting this flash-like intensity, the two compositions are dedicated to the practice of bungkalan, which, for Camacho and Lien, is the embodiment of the irrepressible fortitude of life. A bungkalan site is a garden or plot, which stands for the general practice of growing food on occupied, stolen, or monopolized land. Throughout world histories, the politics of the plot tended to by peasants, enslaved, and colonized people, as well as modern plantation workers, is a shared strategy of survival and resistance against the violent sterility of monocultural ecology. Returning to the garden, understood as both land repair and social repair, would call for an imagining of the revolutionary fire as generative and life-giving.

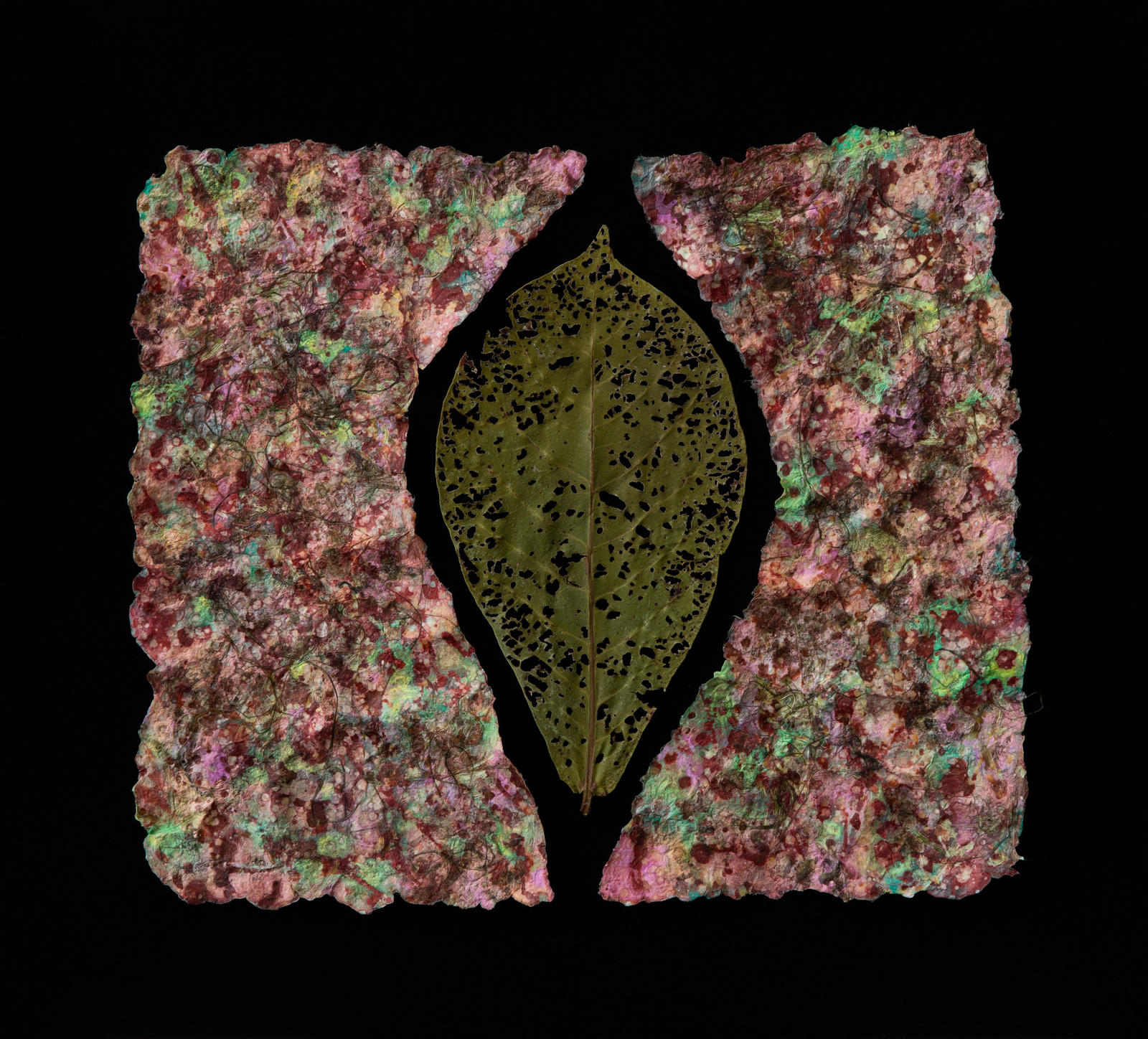

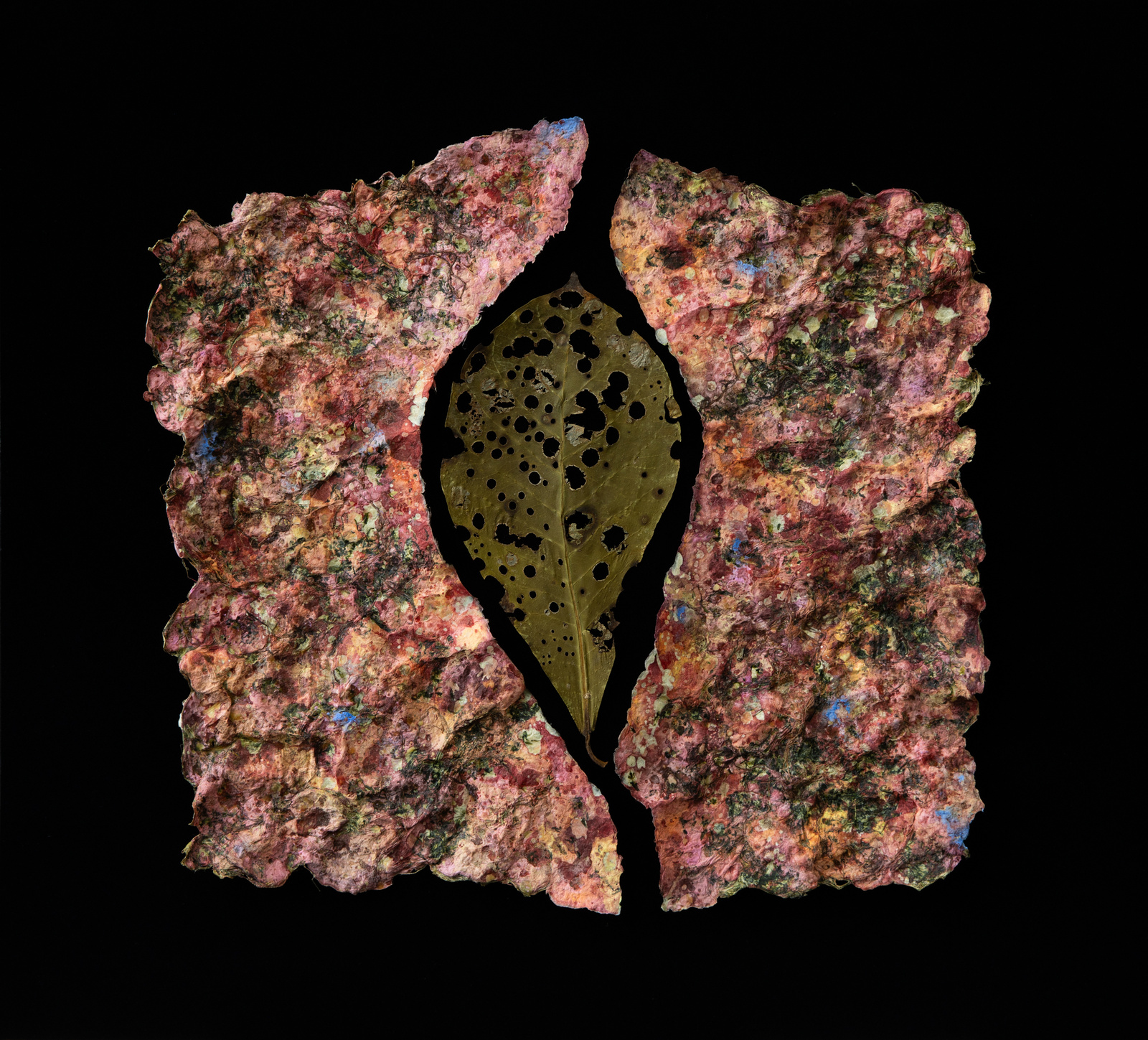

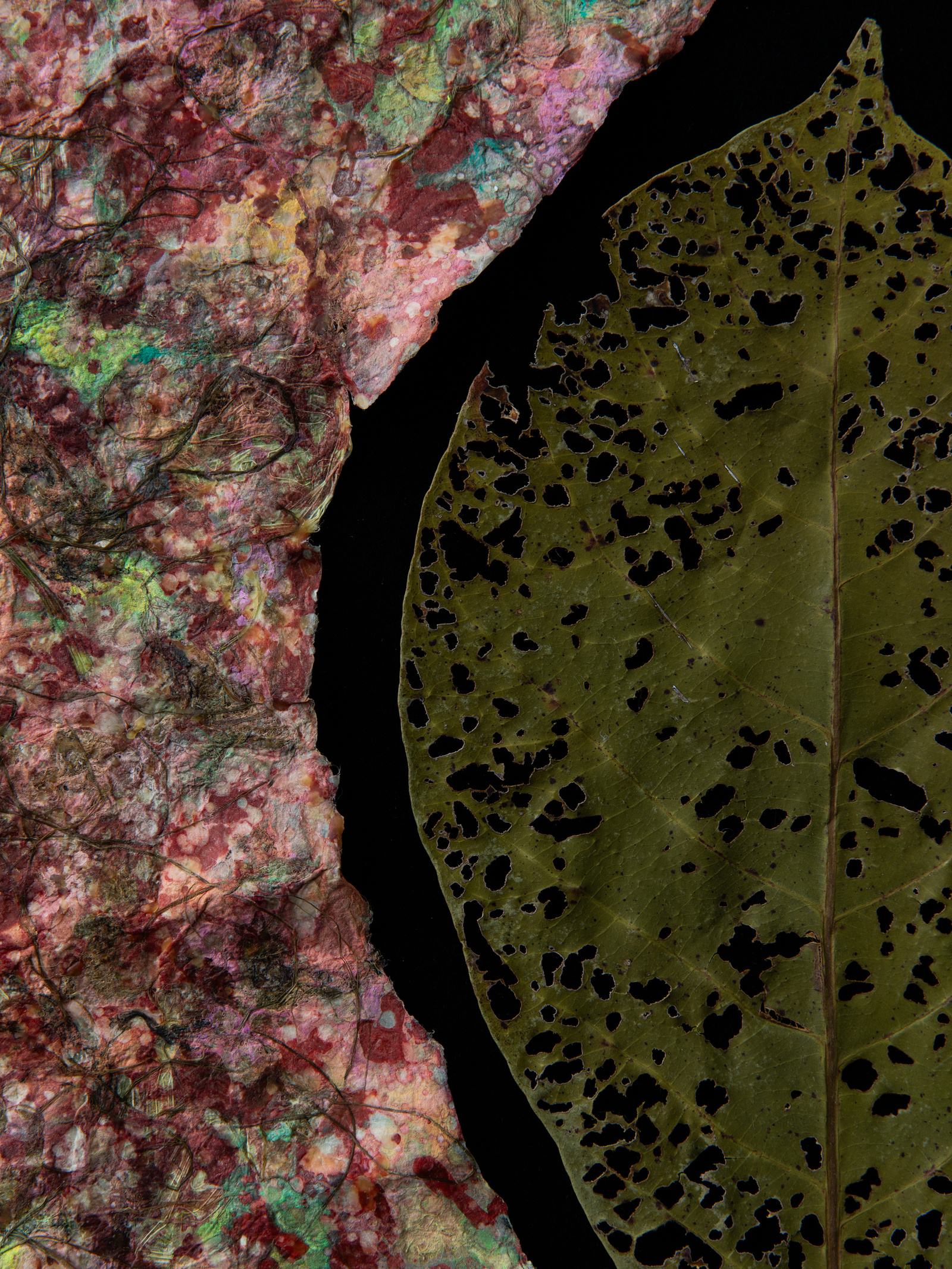

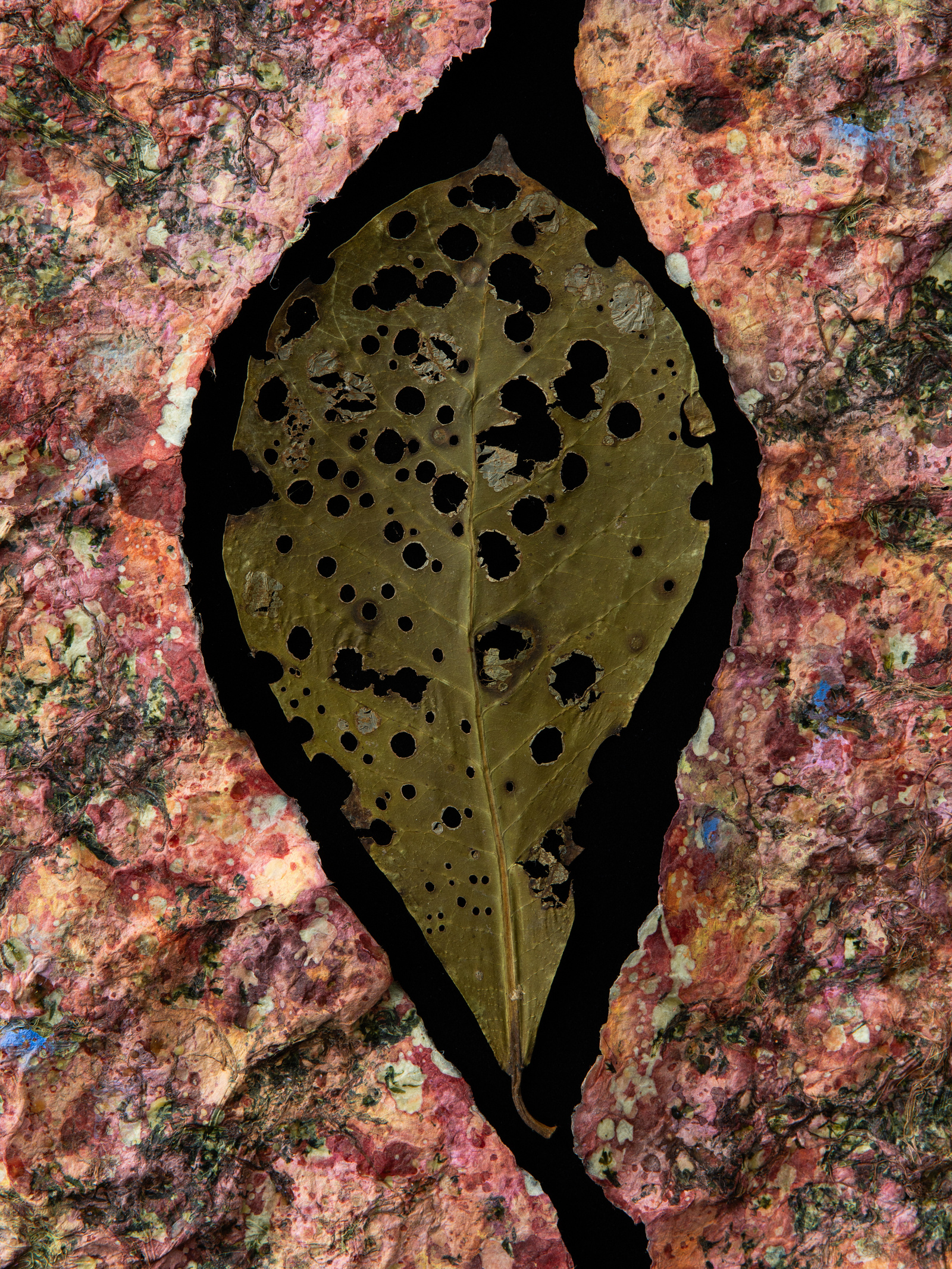

Hunger Leaf (long breath)

Hunger Leaf (flagellation)

Hunger Leaf (curled)

2024

Calophyllum leaf (Bitalog leaf), watercolor, beeswax, abaca pulp, banana stalk, cilantro, nipa, parsley, spring onion

61.6 × 67.9 × 11.4 cm

2024

Calophyllum leaf (Bitalog leaf), watercolor, beeswax, abaca pulp, banana stalk, coconut husk, cilantro, nipa, parsley, seaweed, spring onion, and taro shoots

61.6 × 67.9 × 11.4 cm

2024

Calophyllum leaf (Bitalog leaf), watercolor, beeswax, abaca pulp, banana stalk, cogon grass, cilantro, fennel, parsley, spring onion, and taro shoots

61.6 × 67.9 × 11.4 cm

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (long breath), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (flagellation), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (curled), 2024. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (long breath), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (flagellation), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Hunger Leaf (curled), 2024, details. Photo: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

Responding to the notion of tigkiriwi in the film Langit Lupa—“the hunger that gnaws at the guts”—experienced by plantation workers during the “dead time” (tiempo muerto) between harvest and replanting, the series of Hunger Leaf is constructed around leaves with bug-eaten holes that the artists found on the island. To resist this “dead time,” the workers would occupy and cultivate small plots of land—a practice locally known as bungkalan—in and around the plantation to grow their own food. Riffing on the hole-ridden leaves, Camacho and Lien created the abstract surround—the shape of which recalls a splitted shell or a cocoon—through an accumulation of botanical matter, wax, and paint. This layered ground work stages the scene for an interplay between lack and abundance, between the wound-like absence and the opulent potentials and generosity of the land.

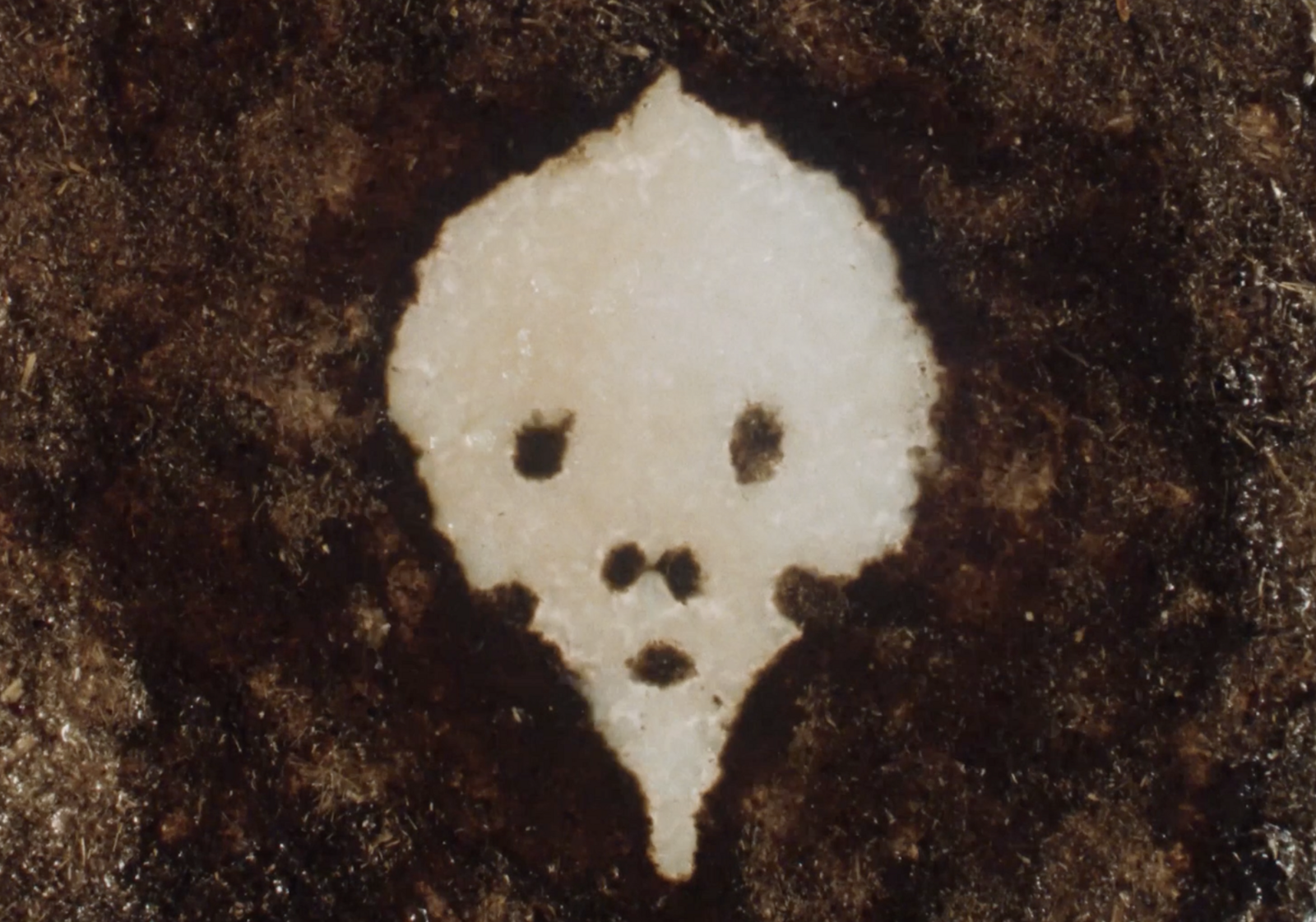

Decomposition Animation

2023

16 mm color film, silent

50’’

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Decomposition Animation, 2023, film stills, courtesy the artists.

Using wet plant pulp and organic matter, Camacho and Lien meticulously crafted the 16mm animation film frame by frame, putting together more than five hundred stills to create the short sequence. This laborious and tactile process evinces an intimacy with materials and a bodily knowledge of their aesthetic potentials. Decomposition Animation shows a loop of metamorphosis, linking symbols taken from folk iconographies and the plantation context to express the cyclical nature of life and death. These motifs make repeated appearances throughout the exhibition, threading the documentary film and the paper compositions together in a tale of transformation. A butterfly is a folklore traveler who goes between the worlds of the living and the dead; out of its fluttering wings emerges a dancing flame, recalling a burning field; a heart wearing a crown of thorns echoes Sacred Heart and The Angry Christ, which turns into a beating organ, dissolved in the symbol of love; a leaf is riddled with bug-eaten holes like bullet holes from a machine gun; death is a return to soil . . . The cycle repeats.

Langit Lupa

2023/24

Digital video, color, sound

56’21’’

Enzo Camacho & Ami Lien, Langit Lupa, 2023/24, film stills, courtesy the artists.

The experimental documentary film Langit Lupa centers around mourning and remembrance in the wake of the Escalante Massacre. On September 20, 1985, in Escalante’s town center on the plantation island of Negros in the Philippines, state-affiliated paramilitary troops opened fire on civilians engaged in a peaceful demonstration—small farmers, sugar workers, fisherfolk, students, and people from other walks of life had come together to stage a protest calling for land reform, labor rights, and an improvement of living conditions on the island. At least twenty protesters were killed and many more were injured. What happened in Escalante was not an isolated incident of state brutality and political repression under Ferdinand Marcos’s totalitarian regime, whose influence prevails today due to his son’s ascension to power. The ongoing murder and detention of land activists and farmers and the recent silencing of public commemorations of the massacre all speak to an oppressive present, haunted by the terrible legacies of the historical subjugation of the land and its people under colonial and imperial rule. The plantation system itself is one such persistent residue that the state—through whatever means possible—seeks to uphold.

Langit Lupa brings together testimonials of the survivors, whose recounting of the violent tragedy is juxtaposed with footage capturing the monocrop landscape and local community’s lives in the interstices between sugarcane fields, punctuated by abstract sequences of flickering shapes drawn from foraged materials on the island. These sequences are created via the phytogram technique, which uses the organic chemistry of plants to develop photographic images indexing inner structures of vegetal tissues and veins. Through this imaging process, botanical matter becomes both the conditioning vehicle and the final object of spectacle. It offers up material possibilities for its own revelation. Accompanying the voices that articulate unspeakable horror and loss, the microscopic choreography of plant life plays a crucial role in the impossible task of narrating violence and its aftermath. Its visceral effect in the storytelling embodies an innate connection between flora and folk, between crimes committed against the land over centuries—“a massacre of the jungle”—and crimes committed against the people, both constitutive of the continuous project of (neo)colonial earth-writing.

The title of the film, Langit Lupa, which translates to “Heaven and Earth,” refers to a Philippine nursery rhyme for a children’s game that ends with the line “Who will leave your mother’s place?” Does departure from a mother’s place allude to the loss of home and means of sustenance, the severance from land and soil, the painful disruption of belonging? In a coastal village near Escalante where the artists resided and worked for months, they forged bonds with local children through games and papermaking workshops and later came to learn that some of their elders had participated in the 1985 protest. One scene of those children at play was filmed in the village cemetery where Robena Franco—the youngest martyr of the massacre—is buried. Here, at a site where “visiting our dead is a family affair,” Camacho and Lien staged a procession with the children, echoing an annual commemorative ritual performed by the survivors at a local church that the artists had witnessed. Langit Lupa shows how memories are kept alive among the communities and beyond, as a bereaved mother said, “I wish I didn’t have to remember [...] Until I die, I will never forget.” Here, remembering is not understood as a choice, but a difficult demand for the return to a renewed place, transformed by the defiant insistence on survival and hope.

Text by Nan Xi