Lukas Luzius Leichtle

Eindringling

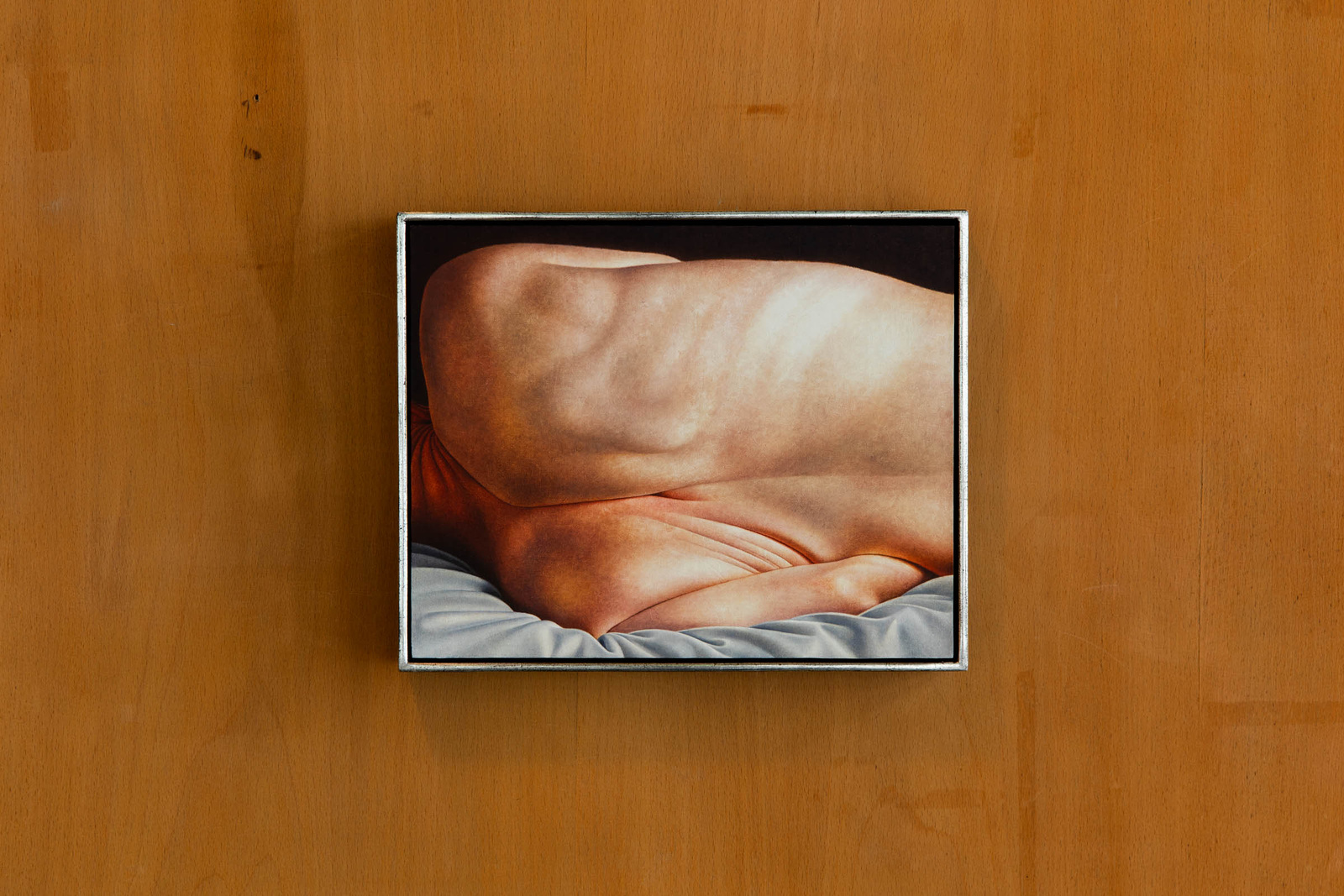

Lukas Luzius Leichtle, Eindringling, Exhibition views, CCA Berlin, 2025. Photos: Diana Pfammatter/CCA Berlin

In 1991, Jean-Luc Nancy’s heart gave out. A stranger’s heart was grafted into his body and the philosopher went on living for another three decades. To stay alive, he had to take medications that suppressed his immune system to prevent his body from rejecting the foreign organ, but the same drugs also gave him cancer. This visceral experience gave rise to a series of reflections on the inherent strangeness of bodily existence, published in an essay titled “L’intrus (The Intruder).” He writes:

In a single movement, the most absolutely proper “I” withdraws to an infinite distance . . . and subsides into an intimacy more profound than any interiority . . . The truth of the subject is its exteriority and excessivity: its infinite exposition.[1]

Like Nancy, Lukas Luzius Leichtle is preoccupied with a particular intimacy arising from the breaches and leaks between inside and outside—the disturbing intimacy of border failures and permanent gaping. Skin folds call to mind surgical incisions or distant horizon lines; a hand, resembling an inner organ, probes the surface of a back; nails burst out of the flesh; fingers curl into an orifice. At these strange sites of intrusion, one confronts an internal alterity of the self—with the fundamental porosity (and perversity) of life. “I was no longer in me.”[2] In other words, I am always already a stranger in my own body—an “I” that can never fully or comfortably identify with its corporeality, who keeps on intruding upon the world and upon itself through constant disidentification.

For Leichtle, the shape and sound of the word Eindringling (German for “intruder”) offer a striking spatial

and bodily sense of “pushing into”—an act whose forcefulness cannot be absorbed or neutralized. Inhabiting the matchbox building with semitranslucent walls,the artist’s new body of oil paintings is spread across five cellular rooms, creating a choreography of the gaze that turns viewers into intruders, their sightlines into scalpels.

It begins with a movement of inversion: Father’s Sleeping Shirt (2025). A threadbare garment turned inside out, its well-worn folds mapping the inverted landscape of an absent body. Standing before it seems to allow a suspended inhabitation of the space between skin and clothes—that flattened threshold that is neither outer nor inner. One steps into the shoes of the anonymous figure in the background of Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ (ca. 1450), head caught inside a half-peeled shirt. The collar circles out a void into which the outside world recedes—a dead-end trompe-l’œil that leads to nothingness behind the wall or, perhaps, into a dormant field of potentiality. The blank spot bares the oil ground Leichtle uses to prime the linen, preparing for vision to seize what is yet to take shape.

In Leichtle’s practice, skin—understood as “infinite exposition” rather than enclosure—is obsessively and relentlessly worked to an excessive state of refinement. The texture of the canvas, and the intensity with which Leichtle labors over it—wears it out by using sandpaper and an electric nail filer to scrub away layers of paint—produce an uncanny tactility that ties together matter and form. In Untitled (December) (2025), Leichtle paints the part of his own torso never directly visible to his eyes. This establishes a voyeuristic and estranged relation to a self born and trapped in the contortions of flesh, while simultaneously gazing at its own captivity. Here, the artist’s body is not sublimated into a Renaissance ideal. Though tapping into its aesthetics, the deliberate alienation—achieved through the carefully cropped composition and rendering of flesh and folds—prevents the figure from sliding into a representation of neutrality. The body remains visually bound by sticky signifiers such as “white” and “male” while also resembling a cut of meat. Stretched taut across the expanse of the canvas, the captured skin becomes an abraded surface against which the subject’s claim to sovereignty and autonomy wears thin.

In one move, the “I” is displaced onto the skin’s surface; in another, it is expelled further outward—into the corner of a bathroom. If the first attempts to create a sense of opening without cutting open the skin, the second evokes corporeality without the presence of a body. For Fuge (6) (2025) and Fuge (7) (2025), Leichtle applied verdaccio as a preparatory layer—the green underpaint used by Italian Renaissance artists to render flesh. A lifelong compulsion to wipe water from bathroom walls in fear of mold has led to an intense observation of the materiality of tiles and the fugue in-between, where moisture gathers. Everything remains fully visible in the tight corner, yet an odd sense of depth lingers, as if something were hiding out of sight. The corner pulls one in, its slightly warped perspective dizzying. The sickly tones and imposing grid structure stir up feelings of repulsion and paranoia, like the frozen panic of a hypochondriac—desperate to flee but pinned to the spot by a fear (and fascination) of “intruders”: germs, stains, diseases, and mold. The tiles close in around a missing bather. This art-historical trope of cleansing, however, is reimagined here as body horror without a body.

Julia Kristeva attributes the feelings of horror, disgust, and desire associated with bodily waste to an encounter with the abject, which arises at the boundary between the living and the nonliving, subject and object: "It is thus not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite."[3] In Leichtle’s visual world, the abject often emerges at the extremities of the body, where the clear distinction between self and world collapses. Fingers and nails form an exemplary composite site, where living flesh and dead shells meet, one pushing into the other at the crescent-shaped cuticles—intruding, fraying at the edge. In various studies of hands, Leichtle bends his fingers to the limit of their mobility, seeking charged positions where the appendage asserts its alienness precisely in the strain of its constraints.

In Gap (2025), two hands close around each other to form a tunnel; in Probe (1–3) (2025), fingers twist into enlarged statues in a series of three. The horror of these fingers begins with looking too closely, triggering a fear of enormous objects or things magnified to an abnormal scale. Each wrinkle becomes a slit or valley, each curve opens into a niche of flesh. The metallic structure of the nails clashes perpendicularly with the folds of the skin. A double sensation of touching and being touched ripples where the fingers press into one another. Intrusion is also body turning against itself, until its homogeneity crumbles, giving way to the terrifying truth of multiplicity.

Sight and touch converge in an act of intrusion famously in Caravaggio’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (ca. 1601), where the doubting apostle pokes his finger into the wound of the resurrected Christ. This barrier breach is echoed in Umstülpung (2025), where a figure is caught in a twisted posture: one hand reaching behind the back, pressing beneath the shoulder blade as if probing into a cavity. The hand stands in stark contrast to the overexposed skin, hanging heavy like a fruit or a transplant. The torso opens a deep gulf for the hand to enter, drawing our gaze inward but not yet breaking open the skin. Another inversion seems about to occur, as though the hand could flip the body inside out.

These visceral engagements with the body’s ambiguity do more than provoke disgust or fascination. By causing disturbance at the borders of self, Leichtle’s works reveal an “I” in constant fluctuation through intrusion—an intrusion that is not antithetical to our bodily existence but constitutive of it. If “I think, therefore I am” inscribes a hierarchy in which body is subjugated to mind and reduced to property guarded, regulated, and possessed by the master subject, then the figure of the intruder acts precisely to unsettle this order. Our age is defined by an endless search for alternative conceptions of the self in relation to the other, with bodies emerging as contested territories for this query. For Leichtle, what is at stake is a cultivation of sensitivity to the otherness within the familiar—to the in-between and the abject, where living is felt most intensely and vividly—an ontology of strangeness, like when Nancy wrote, “I am, because I am ill.”[4]

—— Nan Xi

[1] Jean-Luc Nancy, The Intruder, trans. Susan Hanson (Michigan State University Press, 2002), 12–13.

[2] Nancy, The Intruder, 4.

[3] Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (Columbia University Press, 1982), 4.

[4] Nancy, The Intruder, 4.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a public program including guided tours, a concert performance, a workshop for children, and a lecture.

Curators: Fabian Schöneich with Nan Xi

Production: Franz Hempel

Lukas Luzius Leichtle (*1995, Aachen) graduated from the painting department of Kunsthochschule Berlin Weißensee in 2024, where he attended the classes of Friederike Feldmann and Nader Ahriman. Leichtle lives and works in Berlin. Notable presentations include solo exhibitions All Thoughts No Prayers at NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein in 2023 and Echo Chamber at White Space Beijing in 2025.

Leichtle’s practice is rooted in his intensive observation of intimately staged motifs through the medium of painting. Driven by an interest in the relationship between human experience and its physical, bodily reality, the artist seeks moments in which these psychological workings manifest in visual form. By building up his paintings through successive applications of transparent glazes, Leichtle emulates the physical structure of human skin on canvas. These diaphanous surfaces are treated with abrasive tools such as sandpaper or manicure milling cutters, pushing the paint into the scratches of the underlying structure and exposing the materiality of the primed linen. This approach blends the illusory potential of representational painting with the material reality of paint on canvas. Body parts are compressed, tested for their limitations, and overexposed under Leichtle’s attentive examination, inviting the viewer to experience the supposedly familiar anew.